Cold Events and Global Warming

The recent extreme cold event in the US has raised questions about its relation with human-caused warming. In the public discussion I’ve noticed the broadly held misconception that global warming increases those events or makes them worse. I don’t think there is solid scientific evidence for this. To the contrary, I think the evidence indicates that, if anything, those events become less extreme and less frequent with global warming. So what causes this wide-spread misconception even from normally reliable and well-informed media outlets and public figures? Before addressing that question let me quickly document the discrepancy between media and science.

Media

On tonights PBS Newshour Bill Gates said “Well, the world has had these wind patterns that keep cold fronts from up in Canada from coming down into the Midwest. And as those wind patterns break down, it just makes events like last week substantially more common.” From her lead-up to the interview it is clear that interviewer Judy Woodruff holds a similar belief: “All of us face the risk that extreme weather events like the recent one in Texas will become more common and more destructive occurrences because of climate change.”

A few days ago Naomi Klein wrote in the New York Times “It was the very sort of freakish weather system now increasingly common, thanks to the unearthing and burning of fossil fuels like coal and gas.” Not long before that Antonio Guterres, the UN Sectetary General, said the following: “Well, we are having global warming, clearly, as an average in the world. But at the same time, as we are having global warming as an average, another impact of climate change is that all storms, all oscillations are becoming more extreme. So, if you look at hurricanes, if you look at storms, but also if you look at heatwaves and coldwaves, they are becoming more extreme because of climate change. Climate change amplifies.”

Science

Global warming does make heatwaves more common and more intense, but it makes cold extremes less common and less intense.

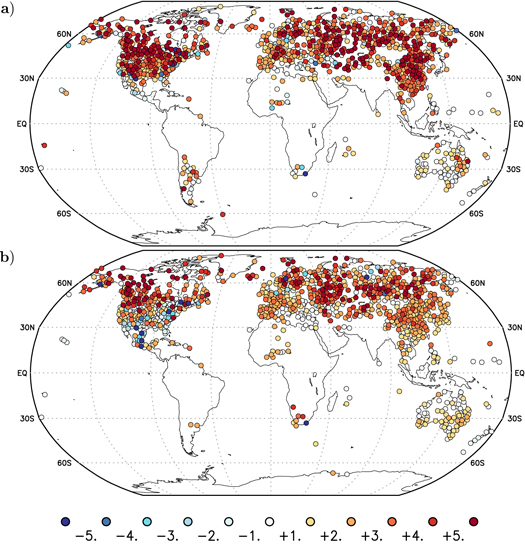

The latter is illustrated in the figure below, which is from this paper.

It shows a regression of the observed temperature of the coldes day in the year onto a smoothed version of global average temperature. Since global average temperature has increased red colors indicate places where the temperatures of the coldest day have also increased. Since almost all places show up in red it means that cold waves have become less intense. (The top panel uses daily minimum and the bottom panel daily maximum temperatures.) The same paper also shows that cold waves have become less frequent.

This does make good physical sense, because global warming leads to warming almost everywhere and at any time of the year. This includes winter and times during which it is particularly cold. So given this simple physical reasoning and observations that show the opposite, where does the idea come from that global warming could make cold events worse? There have been various speculations in the scientific literature. A popular one suggests that more warming in the Arctic due to sea ice loss would weaken the polar vortex, which is the belt of strong winds surrounding the Arctic that acts like a barrier. A weaker vortex would then become more wobbly, which would allow cold polar air to penetrate further south. Although interesting for scientists, this theory is very controversial and no consensus exists within the scientific community. This was pointed out recently by Valerie Masson-Delmotte quoting from the IPCC’s most recent Assessment Report “Changes in Arctic sea ice have the potential to influence mid-latitude weather (medium confidence), but there is low confidence in the detection of this influence for specific weather types.” One of the issues with this theory is that observations don’t show a wobblier jet stream.

A Science Communication Failure?

So why is a highly speculative theory so prevalent in the public sphere, while the more straightforward and physical explanation is not? I think it may be due to a failure in communicating uncertainty. As climate scientists I think we should avoid communicating highly speculative theories. In communicating with the public it is advisable to emphasize the things we know best, the things we’re really sure about. In the context of cold extremes and global warming this is the observational evidence that, if anything, global warming makes cold extremes less likely. If we omit this and make general statements about global warming increasing extremes and take a long time to elaborate on a controversial theory it can lead to public confusion.